High-level architectures of multilateral information-sharing within the maritime domain in Europe

The complexity of security risks and threats in the maritime domain increases day by day. Irregular migration, human trafficking, drug smuggling, arms trafficking and illegal fishing challenge European sea borders to an ever-growing degree. Maritime routes constitute the most important intercontinental transportation channel, thus making them susceptible for a multitude of misconduct by organised criminal groups operating in drugs, weapons and counterfeit goods smuggling. The importance of maritime security to EU’s strategic interests is indisputable, as almost all external and a significant proportion of internal trade transit via sea routes.

Main vulnerabilities in seaborne trade supply lie in container shipments, and the overall scope of containerised transportation (500 million containers annually) makes the detection of suspicious or security-critical loads a highly challenging task for relevant national authorities. The vulnerability and resilience of global subsea data cable networks and energy infrastructure to external attacks also raise significant concern, as the North Stream pipeline explosions vividly exemplify. Besides security risks, the introduction of new transportation routes, novel detection technologies and intelligent information exchange platforms impact the Member States’ abilities in maintaining an adequate level of Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) or Maritime Situational Awareness (MSA).

To manage the multifaceted risk and threat landscape of territorial waters and the high seas, efficient multilateral cooperation and coordination are essential. They are also crucial prerequisites for achieving required level of MDA/MSA, which refers to the effective understanding of anything associated with the maritime domain that could impact security, safety, the economy or the marine environment as defined for example by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO).

Traditionally, data collection for situational awareness has been a predominantly siloed activity of European and national authorities responsible for different aspects of maritime surveillance, and information exchange between various stakeholders has been technically, procedurally and geographically limited supporting mostly local, national, regional and sectoral approaches for data sharing. For example, the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) has identified 33 different sectoral systems or system initiatives relating to the maritime domain (Figure 1). The sectors range from maritime safety and security to border control and defence. Some of the listed items are already obsolete, such as FIDES, I2C, Perseus and SeaBILLA, which represent European projects completed in the 2010s.

The European Union Maritime Security Strategy (EUMSS) and its action plan highlight the significance of closer collaboration between authorities at national, regional and EU levels in enhancing maritime situational awareness. Above the EUMSS lies the EU’s Strategic Compass, endorsed in 2021, underlining the importance of the maritime space for EU’s strategic integrity and need to enhance EU’s maritime security awareness mechanisms. To realise an effective, real-time and shared understanding of the maritime domain, several EU level initiatives have been undertaken and implemented as visible in the above listing. In the remaining, we address five systems in more detail.

On the civilian side, the Common Information Sharing Environment (CISE), initially launched in 2009, aims to ensure effective point-to-point information exchange between various maritime authorities. Over 300 EU and national authorities are engaged in CISE and benefit from the shared classified and unclassified information generated by existing surveillance systems and networks. Currently, CISE is transitioning into operational status with the process being led by the European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA). Together with European-wide implementation, national implementations are also taking place at individual Member States with for example Finland and the Finnish Border Guard aiming to technically integrate and deploy CISE data services in autumn 2022. The project also studies cybersecure exchange of information.

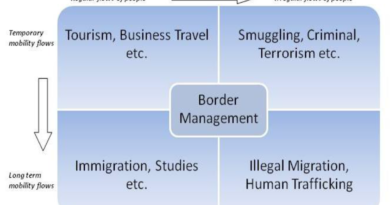

The European Border Surveillance System (EUROSUR) shares similar objectives of enhancing data sharing and cooperation between Member States with a distinctive border security focus on the particular type of information to be exchanged (e.g. data relating to irregular migration, cross-border crime and the protection and saving the lives of migrants). The 2013 established EUROSUR is operated by the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) and is currently in the starting phases of a significant upgrade process. The revision work aims to cater for changes relating to the extended roles and responsibilities of Frontex and the Member States introduced by Regulation (EU) 2019/1898. At the background also lies a EUROSUR evaluation study, performed in 2018, which made several recommendations for improving the functioning of the system and enlarging its scope.

In the defence domain, the Maritime Surveillance project (MARSUR) is directed at creating an information exchange network that exploits existing naval and maritime information exchange systems. The lifecycle of MARSUR extends to September 2006, when it was launched by the European Defence Agency (EDA). The high-level objectives of MARSUR are uniform with CISE having a specific goal in improving the common Recognised Maritime Picture by facilitating exchange of operational maritime information and services such as ship positions, tracks, identification data, chat or images as specified by EDA. At the moment, MARSUR is undergoing its third development phase which aims to develop a next generation system also enhancing its interoperability with CISE and other maritime security regimes. Above all this is the intention to improve MARSUR’s operational use in missions and operations relating to EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP).

Another example of European origin information exchange platform is the Virtual Regional Maritime Traffic Centre (V-RMTC) which aims at sharing selected unclassified information related to merchant shipping that exceeds 300 tons. The Italian Maritime Operation Centre of the Fleet Command Headquarter maintains the V-RMTC hub. Since the launch of V-RMTC, its compatibility with external systems has been assessed, and in 2010, the V-RMTC was extended as a Trans-Regional Maritime Network (T-RMN). Currently, Navies from 24 countries participate the wider Mediterranean community, including both EU MS (e.g. Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, France, Italy) and non-EU countries (e.g. Albania, Georgia, Senegal, U.K., the U.S). In addition to these, the T-RMN includes 11 Navies from Argentina, Brazil, Cameroon, Chile, Ecuador, India, Nigeria, Pakistan, Singapore, South Africa and Peru. During 2022, the T-RMN community is expected to expand by two new Navies from Africa (i.e. Ghana and Liberia). Ivory Coast, Qatar, Australia, and Japan have also expressed an interest in participating the network.

IORIS (Indo-Pacific Regional Information Sharing) provides one reference point to information exchange platforms outside the European Union. IORIS serves as a planning and coordination tool for maritime operations providing also C2 functions for crisis and incident management. Close to 20 national and regional maritime agencies from 12 countries and organisations in the Indo-Pacific region were using the IORIS platform in 2021. These include Comoros, Djibouti, Jordan, Kenya, Madagascar, Maldives, Mauritius, Philippines, Réunion, Saudi Arabia, Seychelles, Regional Maritime Information Fusion Centre (RMIFC, Madagascar), Regional Centre for Operational Coordination (RCOC, Seychelles), EUNAVFOR Atalanta JOC and EUNAVFOR Atalanta FHQ. IORIS is managed by the European project EU CRIMARIO.

Developing shared international MSA/MDA platforms across a multitude of actors is a complex and long-standing process taking several years to reach full or even limited operational status. Implementing such platforms requires careful orchestration of different external applications, legacy system and databases from various public authorities and other entities, not forgetting the political will, negotiations, agreements and consolidated legal basis needed for their implementation in different operational contexts. Information exchange and data models have to be harmonised, and the roles and responsibilities of participants clearly defined. Practical results have only started to realise towards the late 2010s – for example, MARSUR was utilised to support the EUNAVFOR MED Sophia operation in 2017. Most recently, MARSUR has been used in operations in the Gulf of Guinea relating to the concept of Coordinated Maritime Presence (CMP) of the European Union External Action.

The comparison of the high-level architectures of the selected platforms focuses on how their components are structured and their interrelationships are organised. As the platforms mainly aim at information exchange and MSA/MDA generation, they primarily have a coordinating function instead of providing centralised command which would direct the use of included assets. CISE represents the most comprehensive platform as it engages the largest composition of heterogenous stakeholders ranging from local maritime agencies to national Navies and European agencies. CISE, EUROSUR and MARSUR are managed and maintained by European agencies, while V-RMTC/T-RNM is hosted by a national military organisation. Information exchange happens mostly on a voluntary basis, except with regards to the EUROSUR framework, in which National Coordination Centres (NCCs) are required to distribute information that is necessary for the creation and maintenance of European Situational Picture and Common Pre-frontier Intelligence Picture. However, to date, this has not been comprehensively achieved.

All examined platforms implement a service-oriented approach for architecture design. For almost two decades, service orientation has been a customary architectural concept also within the security-critical domains, as it enables the integration of processes, functionalities and data from heterogenous systems into structured and interoperable services while safeguarding the integrity of legacy systems. At the core also lies the idea of reusability; information units collected within national surveillance systems or other systems relevant for situational awareness are made available to external stakeholders with coinciding information needs.

The key building blocks for information exchange are similar across the platforms including a central network and a set of nodes that serve as hubs and gateways for messaging and exchange. The legacy systems may be directly connected to the platforms through individual nodes or through shared nodes. However, some platforms still require manual information entries. In addition, there may be a national node in place for redistributing data among legacy systems. All platforms aim at sharing both unclassified and classified data, however, practical implementation towards this direction is still ongoing. If non-EU stakeholders are engaged, particularly the sharing of classified information requires careful consideration and detailed clarification, as all data shared within a platform may become accessible for all participants.

Figure 4 provides a general schematic representation of MDA/MSA system architecture. The data-sharing node is an important interface that handles communication with other MDA/MSA systems that could lead to a development of a harmonized platform for sharing critical data among various exiting systems. The data-sharing node encapsulates underlying system complexity and provides standardized common application programming interfaces (APIs) for easy access to the data. It also holds the metadata, which represents data about data. The metadata defines different aspects of the data and summarizes what data is available for other systems to utilize. MDA systems include the interfaces to the national legacy systems and to the private or government data collection platforms. Additional value in the future is gained from the enhanced of multimodal combination with AI and data fusion strategies to detect criticalities and from the comprehensive dynamic visualisation of MDA with accurate up-to-date information.

Transnational data sharing within the domain of MDA/MSA involves a multitude of actors and platforms, which could leverage benefits of existing frameworks and standards to design and implement data-sharing nodes. The European Union has devoted significant resources and drafted policies to promote data sharing initiatives and platforms across its Member States. Two of the most recent, advance and complementary initiatives are International Data Spaces (IDS) and Gaia-X. The IDS is a European reference architecture for data sharing, and it provides standards and a reference architecture to establish a decentralized platform for secure and trusted data sharing. The Gaia-X offers a software framework/standard to connect existing cloud services and provide opportunities to create a federated digital infrastructure for Europe and ensure data sovereignty and interoperability. Adopting these novel approaches into next generation MDA/MSA platforms and validating their added value and fitness-for-purpose for the civilian or defence domains still requires extensive research.

by Laura Salmela, Adil Umer and Sirra Toivonen of VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland Ltd